Part II: The Cultures of Risk—Financing the Startup of Start-up Communities

Guest Post By Tom Nastas – Scaling up Innovation – (VC, Mentor, Blogger)

Tom Nastas a 25 year VC veteran in US, int’l and emerging markets wrote a series for Startup Rev on the ‘spark’ which sparked the startup of Russia and how the development of start-up communities in emerging markets are shaped much more by the cultures of risk vs. what we investors and entrepreneurs face in the USA. An interesting read, below are the individual posts and content for each one.

Subjects in this post:

1.) The Cultural Divide: What Investors ‘Buy’

2.) What Investors Fear

3.) The Culture of Venture Capital: Friend or Foe?

Last time in Part I, I discussed:

1.) First, Three Definitions

2.) The Russia Tech Scene

3.) Growth in Russia

4.) What Changed for Growth to Emerge

5.) The Spark that Ignited the Start-up of Russia

Read the Introduction to the series.

Summary from Part I: Beginning about 2006, innovation became a priority of the Russian Government to diversify its economy from oil/gas with its multi-billion dollar investments in the Russian Venture Company and the Russian Corporation of Nanotechnology. Even with these investments, the needle of tech investment crept up ever so slowly in venture stage companies.

But everything changed beginning in the 2nd half of 2010; Russian entrepreneurs cloned US business models in Internet e-commerce, social and mobile with 20+ startups attracting more than $400 million in less than eighteen months through 2011. For 2012 investment in start-ups and venture stage companies is estimated at between $800 million to $1 billion.

The ‘take-away. Russian entrepreneurs demonstrated that cloning established Western Internet business models and localizing them for the domestic market captures growth. This was what domestic investors needed to open up their pocketbooks and spark the startup of Russia.

Ok, so, uhm—what’s so revolutionary about entrepreneurs cloning the ideas of others and investors financing start-up clones?

To answer this question, I discuss the culture of risk in the developing countries and how it impacts the behavior of local investors and their willingness to finance seed and early stage tech business models. Then I contrast how their investment behavior differs from investors in the developed countries.

The Cultural Divide: What Investors ‘Buy’

American tech and start-up entrepreneurs ‘sell opportunity’ to raise money. This works great in the United States since angel investors and venture capitalists are comfortable with risk, ambiguity and uncertainty, and willingly pay the costs of failure when business models don’t work, founders pivot and start-ups evolve into something different from entrepreneurs’ initial intentions.

American tech and start-up entrepreneurs ‘sell opportunity’ to raise money. This works great in the United States since angel investors and venture capitalists are comfortable with risk, ambiguity and uncertainty, and willingly pay the costs of failure when business models don’t work, founders pivot and start-ups evolve into something different from entrepreneurs’ initial intentions.

Except for the very few, most local investors from Manila to Moscow and from Shanghai to San Paulo approach risk differently. Sure, opportunity is required for the financing of ventures. But the risks of execution are more importance as the deciding factor since emerging market countries are opaque and with their lack of transparency—invisible risks and obstacles can cause even the most experienced investors to lose their entire investment: Capital preservation drives financing decisions.

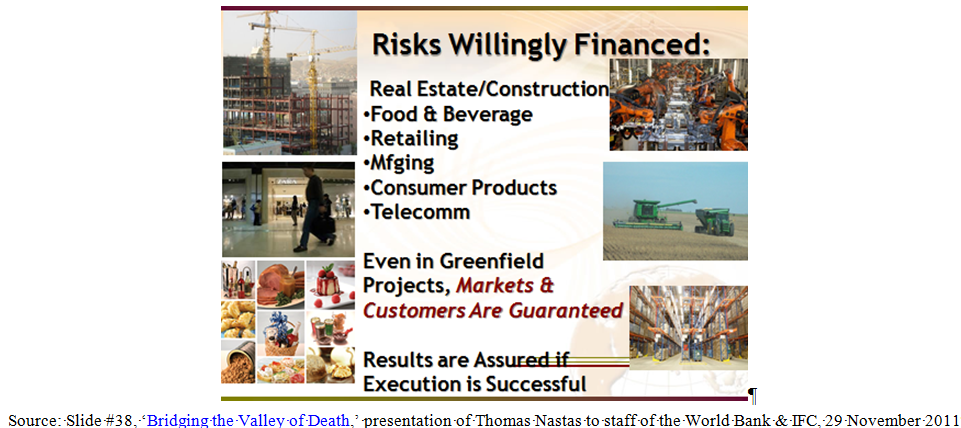

Consequently they buy ‘risk’ by investing in the known and understandable; businesses and projects with markets and customers a 100% guarantee, where the risks of the investment are in the execution of building a factory or constructing a warehouse, creating a bank, establishing a chain of shops or restaurants as examples. These are the uncertainties they have dealt with as businessmen and investors, and have the experience to help entrepreneurs solve—avoid.

What Investors Fear

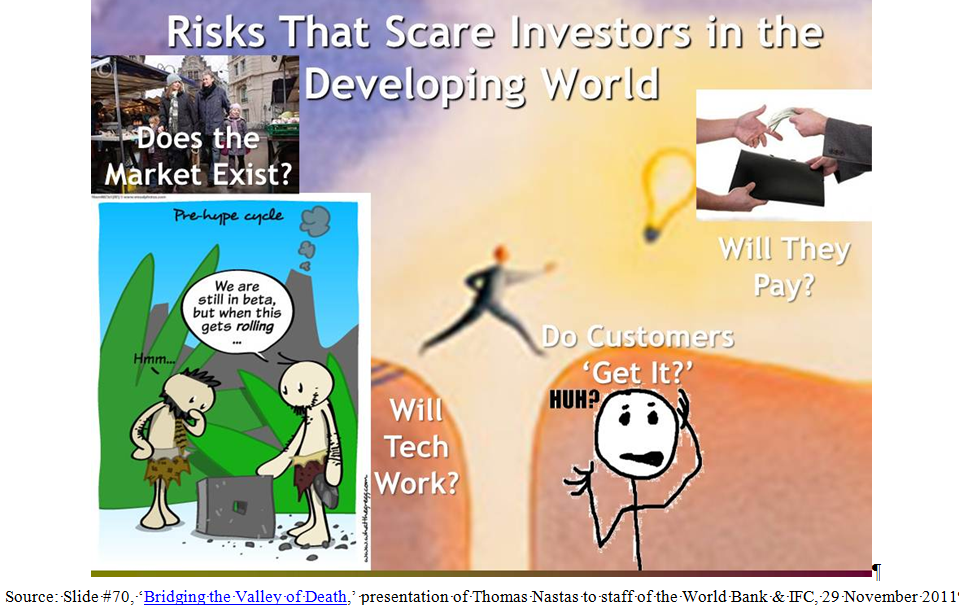

The risks of financing innovative firms, i.e., does a market exist, will customers buy, achieve promised performance—often technology based—are uncertainties too great for domestic investors in emerging markets since they add additional layers of risks to those of execution and involve a different sort of risk assessment—skills and experiences they frequently lack.

Clones overcome these fears since many generate revenues immediately, some from day #1, demonstrating that a market exists, the tech works, customers show up and pay. With these risks behind the venture, the way forward is managing execution—risks that local money in emerging markets ‘buy:’ the tolerance of emerging markets investors for the US model of entrepreneurial experimentation, trial and error and the funding of pivots is zero.

Why is this so? And how do we use this culture of investor risk-taking as our ally, to make amazing things happen; more entrepreneurship, more innovation and more investment for the start-up of start-up communities not only in Russia but throughout the emerging world from Chile to China, Kazakhstan to Kenya, India to Indonesia?

The Culture of Venture Capital: Friend or Foe?

To obtain a deeper understanding why entrepreneurs and investors behave as they do in the emerging markets, we must look at an unlikely place to frame this discussion: Silicon Valley.

“Silicon Valley is the only place on Earth not trying to figure out how to become SiliconValley.”[1]

Silicon Valley’s greatest attribute is not its ability to finance the future and failure, but investors’ attitude to risk which shapes their risk taking, their acceptance of ambiguity and uncertainty to early stage tech deals, thereby attracting entrepreneurs with the wildest (and craziest) ideas.

This behavior to risk is exemplified by the 2-6-2 distribution of returns rule.[2]

For every ten investments made by investors, two fail with all money lost, six return the original investment + a low to modest rate of return, with the remaining two generating breathtaking profits (Facebook, Google, Apple, Cisco, Oracle, Instagram and Microsoft as examples). These ‘superwinners’ as they are called, produce the superior rates of financial return that compensate for losing investments and slightly profitable ones.[3]

Of course one never knows in advance which investments will be superwinners or also-rans. Since Silicon Valley investors know that statistically they’ll invest in their fair share of superwinners, they have the confidence to finance the wild and crazy, a few which become successes. Superwinners breed or attract others to launch start-ups. As more entrepreneurs enter the market, the number of new companies financed increases with less time required by investors to make the investment decision. More choice is what investors need since for every one investment, 99 are rejected;[4] to consummate ten investments (the 2-6-2) an investor needs to see 1000 opportunities. More choice attracts more capital to the start-up community as other investors jump in to finance the next set of superwinners. The start-up community prospects and perpetuates to a thriving ecosystem.

Many superwinners did not start on the path to greatness, and they only found it after experimenting with different business models until they hit the bulls-eye; others started down a path only to change direction—pivot—to find what the market and customers would accept. Silicon Valley investors willingly finance early failures since they know statistically, many pivot to success as Google, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, PayPal and others did to achieve superwinning status. While it may seem counterintuitive, investors must finance failure since without them they are not taking enough risk.[5]

It’s this willingness to finance ambiguity and uncertainty that makes Silicon Valley—uhm—Silicon Valley.

The National Venture Capital Association (USA) estimates that in 2010 the US venture industry invested the equivalent of $3,945 per person living in the Silicon Valley area vs. $43 per person in the rest of the US, including other start-up communities like Boston and New York. That’s a 91:1 ratio.[6]

Go to my home state of Michigan and the number falls to $15 per person, a ratio of 263:1.[7] So the likelihood of a Detroit startup raising venture capital in Michigan is more difficult vs. Silicon Valley.

In Russia and other emerging market countries the amount of capital invested/population is even less than Michigan; these regions lack the quality and quantity of deal flow that typifies the Valley and local investors are unwilling to fund experimentation, pivoting, trial and error in business model creation. Since domestic investors buy the ‘risks’ of execution by investing in the known and understandable—businesses and projects with markets and customers a 100% guarantee (experimentation/pivoting not necessary)—the chances of superwinners being created and financed is remote: Yet an increasing flow of future ‘superwinners’ is what’s required for local investors to invest in, and for a start-up community to crystalize.

In Russia and other emerging market countries the amount of capital invested/population is even less than Michigan; these regions lack the quality and quantity of deal flow that typifies the Valley and local investors are unwilling to fund experimentation, pivoting, trial and error in business model creation. Since domestic investors buy the ‘risks’ of execution by investing in the known and understandable—businesses and projects with markets and customers a 100% guarantee (experimentation/pivoting not necessary)—the chances of superwinners being created and financed is remote: Yet an increasing flow of future ‘superwinners’ is what’s required for local investors to invest in, and for a start-up community to crystalize.

That is until an event or series of events breaks this cycle to change the trajectory of the market. In Russia it was the early and fast liquidity from the Groupon clone that demonstrated the merit of cloning Western business models plus the IPO of Mail.ru that minted the money for clone investment. With the United States as the engine of start-up creation in the world, it was natural for Russians to copy, localize and paste clones into Russia, to capture the eyeballs and wallets of the Russian consumer. And then—the pocketbooks of investors too.

The chasm between the cultures of risk-taking by local investors in Russia and the risk of start-ups was crossed. Foes became friends. The start-up of Russia began.

“But this is not the only contribution of clones to the startup of start-up communities.”

For Next Time—Part III: The Power of Clones

In Part III, I discuss the multiplier effect in start-up creation that clones have in local market. Clones do more than just build a local network of supply chain partners thereby increasing the # of startups for a startup community to emerge. Their successes impact the DNA culture of investors to risk as they build new experiences in seed and early stage risk. And they do so without taking the risks of opportunity that is normally associated with early stage companies since clones[8] demonstrate that a market exists, the tech works, customers ‘get it’ and pay.

Subjects in Part III:

1.) Drive Growth and Innovation in the Supply Chain

2.) Sidestep the Obstacles that Impede Scaling Up

3.) Controversy of Clonentrepreneurship: Cloning the Idea or Hatching a Start-Up?

4.) Spread of Clonentrepreneurship

Comments, opinions and questions are welcome here or send directly to me at[email protected].

Be well and be lucky.

[1]Quote from Robert Metcalfe, father of Ethernet, founder of 3Com, author, pundit & conference host

[2] Author’s note: The 2-6-2 distribution of returns rule is a term to describe the distribution of investment returns in a venture capital or private equity portfolio. The 2-6-2 rule comes from data collected and reported on the industry’s financial performance over a 40 year period from Cambridge Associates, the National Venture Capital Association and the Small Business Administration (which tracks investments made through the Small Business Investment Corporation program of the US Government).

[3] Author’s note: While the 2-6-2 distribution of returns is an industry average, individual funds will have a different distribution of financial performance, e.g., some might have a result of 4-4-2, others a 1-9-0, others a 0-7-3, etc. Approximately 2% of investments since the 1980s have produced 98% of the financial returns realized in the venture capital industry (USA)

[4] Author’s note: A rule of thumb in the industry. Naturally some firms will be in the flow of ‘better’ investment opportunities and able to transact the necessary number of investments with a lessor number of total deals evaluated

[5] Source, , ‘Brilliant, Crazy, Cocky: How the Top 1% of Entrepreneurs Profit from Global Chaos,’ page 26, by Sarah Lacy